Last May The Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum in New York opened an exhibition called “Manus x Machina”, exploring how fashion designers are reconciling the handmade and the machine-made in the creation of haute couture and avant-garde ready-to-wear. Displaying over 170 ensembles dating from the early 20th century to the present (from Hussein Chalayan to Alexander McQueen, Iris Van Herpen and our own finalist Maiko Takeda), it addressed the founding of haute couture in the 19th century – when the sewing machine was invented – and the emergence of a distinction between the hand (manus) and the machine (machina) at the onset of mass production. Since then it has been an ongoing dichotomy, a love and hate relationship with positive and negative aspects on both sides of the barricades.

When we think of hand-made as opposed to machine-made we immediately make assumptions. The first one perhaps being quality: a handcrafted item will always be superior to a machine-made one. It doesn’t necessarily hold true every time, and for a very simple reason. The quality relies on the ability of the craftsman of course, therefore WHO makes the item determines its quality. And we could probably say the same about machine precision. It’s easy to understand that the same cut made by a more expensive, technologically advanced machine will be better than a cheaper, older one.

et indeed once the ability of the craftsman is out of question certain characteristics are unmatchable. Attention to detail, quality control over every single step of the process – going from the careful selection of materials to the manufacturing techniques – and the uniqueness of each piece coming out of the hands of an artisan are things that cannot be replicated by any machine (not yet at least). There’s something more. The “uniqueness” factor carries in itself a story, a soul which the owner of such item feels in a personal way, as if it establishes a relation with the artisan who made it. It provides that sensation of having something very personal in your hands.

Bespoke is another quality machines still can’t give you though attempts are being made and certainly the future holds exciting new developments in this particular field. But just listen to the sound of the word “bespoke”, it instantly communicates an attention to the individual customer in delivering something that will only be his, made according to personal requests and personal body sizes. Something nobody else has. A real reaction to fast fashion, to thoughtless mass production. Way better in quality, lasting longer (a characteristic which often – and rightly so – people will indicate as sustainable since it reduces waste) and including a story and soul, provided by countless hours in the making. Indeed, there has been a renaissance for handmade bespoke products as a strong reaction to mass produced identical items.

Of course machines do have very strong arguments on their side. We wouldn’t be using them massively as we do. Overall quality might be the key factor defining handmade goods but precision – particularly in repetition – is probably what defines machines. Instruct a machine to cut a material or fabric and it will do so perfectly, for hours and with unmatched speed. Efficiency (the speed being a key factor) is perhaps equally defining. It always takes the mind of a human being to develop the most efficient process but you can be sure that once it’s established and the instruction given, it will be carried out much, much faster. Which brings us to another essential quality: cheaper costs.

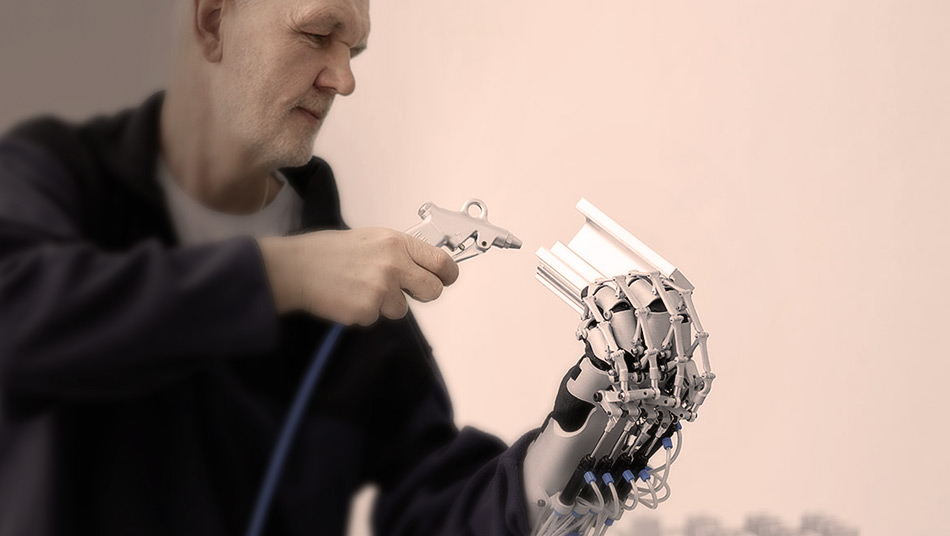

Particularly in fashion the rise of new techniques like 3D printing, computer modelling, laser cutting and ultrasonic welding makes journalist Olivia Fleming of Harper Bazaar rightly question if we should really continue discussing if one is more valuable than the other. And a fashion design icon like Karl Lagerferd goes even further in stating “Perhaps it used to matter if a dress was handmade or machine made, at least in haute couture, but now things are completely different. The digital revolution has changed the world.”

Contemporary fashion is increasingly witnessing human craftsmanship and machine technology as allies, not competitors. Take designer Iris Van Herpen for example, juror at ITS 2016. The biographical note on her website says it all: “Iris Van Herpen stands for a reciprocity between craftsmanship and innovation in technique and materials. She creates a modern view of Hatue Couture that combines fine handwork techniques with digital technology”.

ITS has witnessed countless examples of machine aiding our finalists in the development of their projects, and the ITS Creative Archive, which holds “a history of the recent past with fashion treasures for the future” in the words of former curator in charge of the Costume Institute Harold Koda, houses several examples. Jewerly finalist Annie Berner’s “Digital Deco” collection couldn’t be a more perfect example when it comes to blending artisan techniques with digital tools. 3D printing gave her the opportunity to produce very complicated, chunky pieces inspired by New York Art Deco which play with people’s perceptions. They appear to be made of heavy, precious metals since the finish colours replicate copper, gold and precious stones. On the contrary they are superlight, developed from a cheap plastic powder “cooked” in shape by the 3D printer in thousands of layers one on top of the other. At ITS 2015 the futuristic work of Yang Wang literally amazed us, with his sci-fi collection of pieces that hint at a future when we will not only be wearing technology: pieces might actually be hovering around us, modifying and influencing our halo space. His collection pieces – actual mock-ups of a not too far future – were an actual blend of absolutely modern techniques like CNC paired with the craftsmanship that only hands can give, precisely because he wanted to provide his items with a “soul”, a background story built on the countless hours spent smoothing out by hand his pieces which would provide his items with something more than just a futuristic shape and concept.

Exhibitions like “Manus x Machina” at the Costume Institute in New York and pieces from the unique collection of our ITS Creative Archive trace a direction that is being followed both by renowned fashion designers and future young talents alike: not a competition between artisanship and machine-made goods, rather a close collaboration to find new interesting solutions in both fields and allowing to fill in the gaps both methodologies have. A kind of networking, shall we say. And you should know by now how much we strive for it…

Other articles:

The Seismographer

Your Kids, One Museum, and Lots of Fun – A family day out at ITS Arcademy is an experience not to be missed

18 October, 2024

We were all born to create, and it’s during childhood that this is most evident. Our favourite adult would place a blank sheet of paper in front of us along with…

The Seismographer

The designers of the future are here – If you need a “push” to find reasons to apply, you’re welcome

02 September, 2024

“How to” – perhaps one of the most (if not THE most) asked question on the internet. How to do this, how to do that, how to build, how to make,…

The Seismographer

A Year in Fashion Conservation: Planned work for 2024 by the ITS Collection conservation team.

02 August, 2024

We have already dealt with the huge (and beautifully exciting) work that is the conservation of a unique collection like the one of ITS Arcademy – Museum of Art in Fashion,…