In 1929, the first line of a Vogue feature entitled “The Fur Story of 1929” went like this: “Go without jewels, pocket money, or every-day clothes, Vogue advises, but never try to scrimp on fur. For the fur you wear will reveal to everyone the kind of woman you are and the kind of life you lead.” It gives a very clear idea of what kind of status symbol owing and wearing fur used to be. Before its decline, mainly due to animal rights movements but also to the introduction of its fake counterparts, fur had been a symbol of wealth, even aristocracy, for many centuries.

Mankind has worn fur and leather since its earliest times out of the African cradle to protect from the colder weather conditions as well as from harm. Warmth and durability, very practical aspects which no other material could provide at the time, made them unrenounceable not just for clothing, but a wide variety of other practical uses like shoes, water flasks, helmets, bags and much, much more. To this day, tribes like the Inuit who live in some of the harshest weather conditions on the planet wouldn’t be able to survive without them: their fur garments are so precious they wear them all their lives, often passing them on from one generation to the other.

Sourcing fur and leather would be complicated. You would either have to be a hunter yourself, adding an education in the knowledge of fur and leather treatment after having killed your animal of choice, or have a position of wealth where a hunter would be at your service. Thus, owing fur or leather very soon turned into a representation of wealth.

Different kinds of fur could indicate different social status. In ancient Egypt for instance a leopard skin or lion skin could be worn only by kings or high priests performing ceremony.

Over in Europe, chinchilla, mink, ermine and sable were exclusive to royalty, nobility and high ranking clergy. In some early societies fur, leather and its by-products would acquire a mystical or spiritual power if worn by hunters, soldiers or the ruling classes. In short, fur soon became an indicator of social stratifications and it remained such until the 1980s when the voice of animal rights movements questioning the ethics of such products made itself stronger, with fake fur often providing a valuable option.

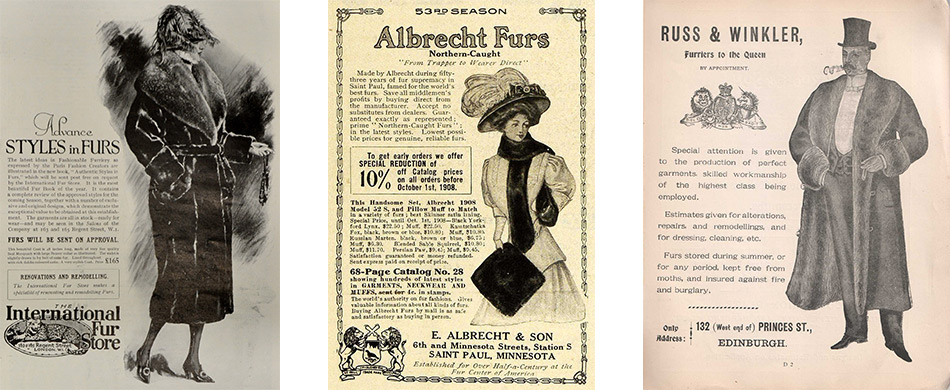

Better and more practical options had appeared on the market way before the animal rights movements raised their voices. Still, the status symbol making fur a luxury good for the wealthy remained. And fortunes have been made over the centuries from the exploitation of fur-bearing animals to satisfy our needs and vanities, even bringing certain species to extinction. Among the first to gain control of the fur market were the Germans since they could easily access the finest Russian furs, particularly ermine which was THE symbol of royalty and nobility. The discovery of the so called “new world”, North America, opened the doors to an almost unlimited supply. Between the 17th and 18th centuries west European manufacturers of fur became incredibly rich. North America remained king in the fur market until fur farms began filling the void. Today, over three quarters of the fur we use comes from farmed animals.

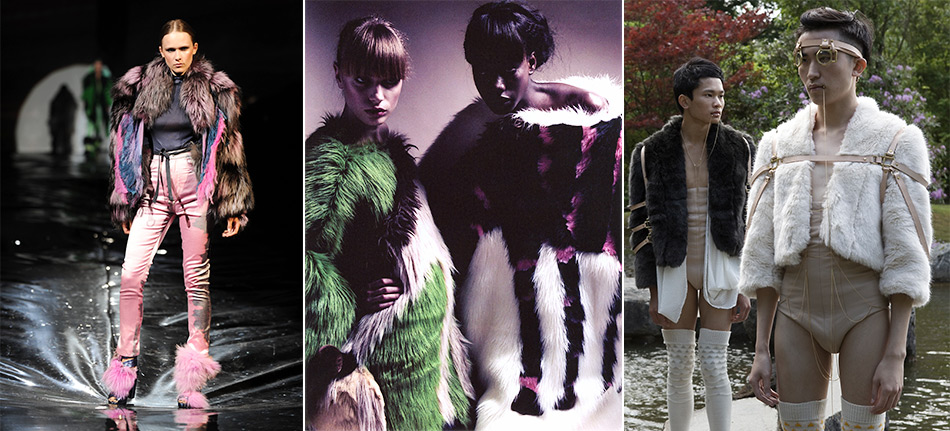

Technology of course radically changed things, as it would do in so many other markets. In the last century advancements in processing pelts made fur and leather available to the masses. This changed fur’s status symbol connotation. Now you weren’t considered wealthy wearing any kind of fur. You were if you wore specific kinds of fur…

It is at this point that fashion designers step in. Until the 19th century designers were hardly perceived as celebrities. But in the late 1800s French designers like Paul Poiret and Jeanne Paquin stepped in the scene, using fur with regularity. They had already established them as celebrities and their use of fur (followed by countless other designers up until today) meant another boost for a fur market which was already slowing down. Fake furs had already appeared on the market as a cheap alternative for women who desperately wanted a real fur garment but could not afford it. In 1924, a fur expert told the Times magazine that “whenever fur becomes fashionable the trade hunts for a substitute, because the girl in Sixth Avenue wants to look like the fashionable woman on the Fifth, and we must help her find her way.” Many say that despite the animal rights movements, it was the cheaper option and overall good quality of its fake counterparts that challenged the real fur market. Apparently, customers were turning their heads to ethics, but not their wallets.

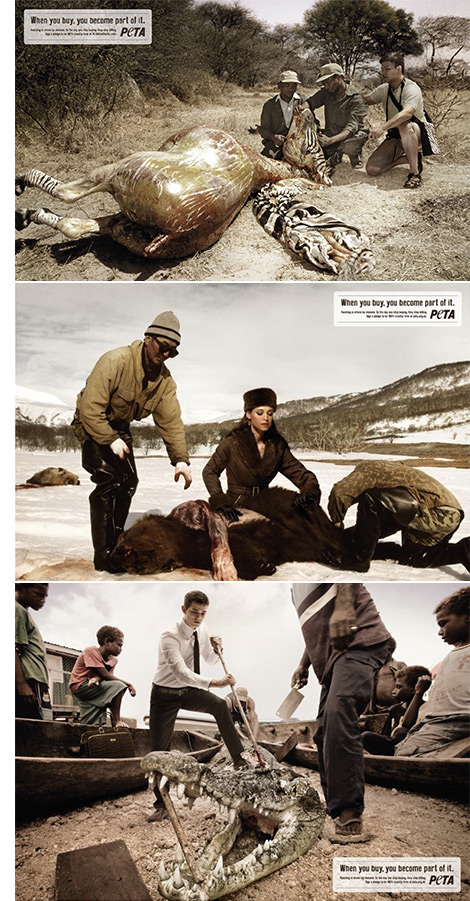

Today, much of the debate on the ethics of fur and leather use still remains. Fur in particular still maintains its position of status symbol. Luckily, organizations like PETA – People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals are doing a lot establishing and protecting the rights of animals through celebrated ads like the “When you buy, you become part of it” campaign of which we include a few examples here. From a functional point of view, synthetic materials often outscore fur and leather by far. But are they more sustainable? Isn’t there a very strong use of chemical processes in the development of nylons, water resistant materials like gore-tex and others? It is a complicated issue. We at ITS have always asked contestants to use fake fur if possible, demanding from finalists they replace real fur with fake alternatives. We’ve never asked to avoid the use of leather by the way, and tanning processes use polluting chemicals which make leathers far less ethical than furs… Animal rights activists, vegetarians and vegans rightly argue that the use of leather is unjustifiable, encouraging the use of synthetic leathers. Yet again, what is the burden carried in the word “synthetic”? The question remains. What is your opinion?